Galtrigill - Croft 9 and the Edge of the Wind

Where the sea remembers, and the land still speaks.

A crofting landscape of stone, story and stillness - open to those who walk with care.

From this quiet corner of the Isle of Skye, a story unfolds: Croft 9 invites you to walk the old paths, where generations have come and gone – leaving little trace, and yet never quite disappeared. The last ones were forced to leave when their homes were cleared and their land turned into grazing.

It is a place that is still lived with, if not always lived in. Galtrigill is a historic crofting settlement carried forward through research, walks, and storytelling. This website is part of that work: to honour what was, to share what remains and to shape what comes next.

What is Crofting?

Crofting is a form of land tenure and small-scale agriculture unique to the Scottish Highlands and Islands. To describe it merely in legal or agricultural terms is to miss its deeper truth: crofting is a way of belonging.

Crofts, Kelp and Control: A History from the Shore

When we think of industry, we picture cities – the smoke, the noise and the endless rows of chimneys. But in 18th century Scotland, industry followed the tide. On remote shores, people gathered kelp and burned it in slow, smoky fires for very little money, and even less choice –– only the promise of survival. Whole communities worked for landlords and not for themselves. Their task was turning seaweed into profit and kelp ash – the alkali used in soap and glass – became a booming wartime industry. To meet demand, landowners reorganised rural life by clearing out tacksmen, dissolving traditional farming systems, and replacing them with small fixed plots that would later be called crofts. These were not crofts as we understand them today as the people had no rights, no security, and no chance at subsistence. Their holdings were too small to survive on – and that was by design. It was estimated that 200 days of off-farm labour were required per family, per year, to make ends meet. In the kelp season – June through August – they had to work day and night in the worst possible conditions. Men cut seaweed with sickles, children dragged it up the shore, women tended fires that burned for 24 hours at a time. The smoke damaged lungs while the oil affected their eyesight. People went blind, and limpets – the fallback food of the poor – died on the rocks from arsenic exposure. The landowner sold a ton at £22 – the labourers received as little as £2. After the Napoleonic Wars the kelp market collapsed – and with it disappeared both the income it had brought and the fragile system that had connected labourers, landlords and coastline. Those who had carried out the work were left behind, often with too little land to live on, and no realistic means of staying. Eventually, many felt they had no choice but to go. Not everyone left though. Some families managed to stay – often on smaller, scattered pieces of land, without secure tenancy and with growing uncertainty about how long they could hold on.

Aftermath: The Birth of Crofting

It was only decades later that crofting became a defined system to stabilise a fragile, emptied rural economy. In the aftermath of the Highland Clearances, displaced families were granted narrow strips of poor-quality land. These crofts, often carved into wind-swept edges of land no one else wanted, became something more than subsistence - they became resilience. A croft was never simply a patch of soil. It was a thread in a wider fabric: of common grazings, shared labour, seasonal rhythms, and inherited knowledge. In the crofting townships of Skye, and beyond, people built lives where governments offered only survival. They raised sheep, grew fruit and vegetables, and passed on language, music, and a sense of place that could not be bought or measured. Over time, crofting gained legal recognition – first hesitantly, then more firmly through reforms like the Crofters' Holdings Act of 1886, with the aim to protect tenants from eviction and to give security of tenure. Crofting was never meant to dominate. It remained a local response to harsh conditions – shaped by patience, place and continuity. Today, it still exists in many parts of the Highlands and Islands. While some see it as a remnant of the past, others continue to live and work within its framework. Crofts are now recognized as crucial to biodiversity, cultural preservation, and sustainable land use.Whether this continues will depend less on policy than on people. Crofting is more than the act of holding land. It means living in relationship with it – noticing what the wind says on an ordinary Tuesday in March, lambing when the rain doesn’t stop, fencing when the frost won’t lift. It is a practice of continuity as much as survival - with those who came before, and those who may yet come after. At Galtrigill, on Croft 9, the work of remembrance and renewal is under way. The croft is part of a township shaped by stone, hardship and resilience. Once home of tenants like Donald MacLeod, whose knowledge of the land and the sea helped a fleeing prince escape, this ground still holds purpose.

Manners Stone Stories

You’ll find the Manners Stone marked on official Ordnance Survey maps – a simple dot with a name, at the very edge of Old Galtrigill on Croft 9.Tradition holds that children were once made to stand on the stone until they had “found their manners.” Others say that standing on it – respectfully or otherwise – might still bestow good behaviour. More colourful accounts include the claim that sitting bare-bottomed on the stone would bring fertility and fortune.

Some suggest that villagers once gathered here annually to bow before the stone – a remnant of older rituals, perhaps meant to encourage a good harvest. The name itself may offer a clue: “Manners” might not refer to etiquette at all, but perhaps to a misheard echo of the Gaelic word manadh, meaning omen. The officially recorded Gaelic name is Clach a’ Mhodha—a stone of manners, custom, or mode. But the island is full of echoes and not all of them translate easily.

At first glance, it is an inconspicuous stone that could easily be overlooked, but its magic attracts people from near and far. Sometimes they don't even realise it. Find out why in the

Workshops & Events

On Skye things don’t happen in a rush. But they do happen – carefully, thoughtfully, and sometimes with tea and coffee. These sessions are not designed to satisfy any formal criteria, they simply take place on a registered croft, which happens to have stories, background, questions, and a kettle.

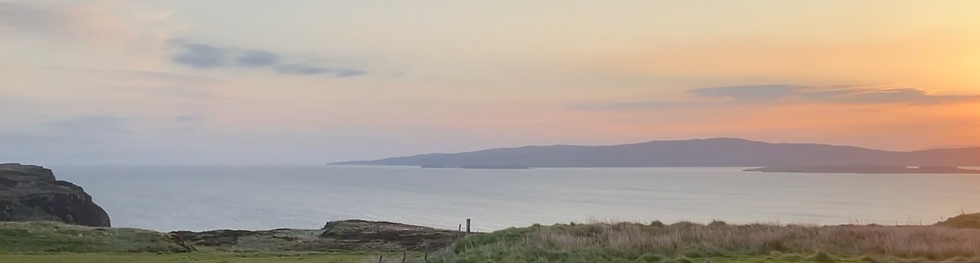

We offer three small-format events in the Skye Orangery: one for those interested in exploring the meaning of crofting, one to explore rewilding and one for those drawn to stories shaped by stone, time, and a very specific view.

Expect no large groups and no microphones. Just a few people on comfy chairs, a view to die for, and a land that still knows how to speak for itself.

Discover the Walks of Croft 9

Embark on a journey through history, nature, and legend with our walking trails at our Croft .

From the solitary Manners Stone to the dramatic cliffs of Dunvegan Head, each route tells a quiet story. As you walk, listen carefully – the magical tones from the Piper’s Cave may seem to echo in the wind. And if you’re lucky, you might catch sight of minke whales moving through the waters below.

Whether you’re exploring ancient ruins or simply enjoying the sweeping views across the Minch,

these walks are an invitation to reconnect – with the land, and with the stories it still holds.

Join us as we prepare the way for future discoveries.

Until then, enjoy the routes at your own pace, with personal requests available.